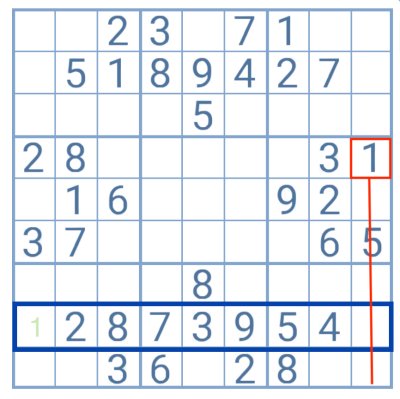

If only three numbers remain and two are incorrect, the final choice is the solution. If we can discover two values that the chain ends say must be ON, one of them is the answer, and the remainder of X may be eliminated from the unit. On the other hand, if one of the two ON cells is ON, we know it’s the solution, and any other possibilities may be eliminated.įinally, the unit will attack if the same number appears three times or more in that unit. If OFF, the solution is the final remaining candidate – however, this only works if the cell has three candidates. Similarly, by locating two ON or OFF digits, we may assault an entire cell. If both ends of the Chain meet on the same digit, that digit can either be discarded or utilized as the answer to that cell if both ends are ON. The endpoints of the two chains are either ON or OFF in each assault. It’s either assaulting another digit (first two rows), a cell (middle two rows), or a unit (last two rows) (last two rows). The beginning cell in this figure is on the left, and an eight has been picked.

We have a contradiction if the chains’ outcomes are the same – another candidate is always ON or OFF.ĭigit Forcing Chains as a Family Before we get into particular instances, let’s take a look at the many sorts of attacks that make up this family. We look at the effects of a candidate being ON and then OFF in the strategy Forcing Chains, a group of candidates in a cell being ON (Cell Forcing Chains), or a number being ON in all occurrences in a unit (Unit Forcing Chains). For example, when a candidate X is switched ‘on,’ all other candidates it can perceive are turned ‘off.’ If there is only one candidate left in the unit that it can see, it may turn on another candidate while it is in the ‘off state. They’re built up of chains (or, more technically, Alternating Inference Chains), which are basic ON – OFF – ON – OFF outcomes. It was the first of a sequence of approaches called Forcing Chains.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)